In April 2019, New York passed a first-in-the-nation congestion pricing law to reduce traffic gridlock in Manhattan’s Central Business District (CBD), while also hoping to raise $15 billion to fix New York City’s subways and commuter rails. The MTA Reform and Traffic Mobility Act (the Act) requires the MTA’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority to design, develop, build, and run the Central Business District Tolling Program (CBDTP), commonly referred to as congestion pricing.

Congestion pricing is phase 3 of the Fix NYC program, a three-phase plan to reduce congestion and raise revenue to fix NYC’s ailing subway and commuter rail systems. Phase 1 called for increasing mobility by investing in public transportation improvements, heightened traffic enforcement in the CBD, addressing bus congestion, and overhauling the parking placard program. In phase 2, the state reviewed revenue options to fund transit improvements and implemented congestion surcharges on for-hire vehicle (black cars, limousines and liveries) and taxi trips below 96th Street starting in February 2019.

Congestion Pricing Parameters

The CBDTP has two purposes: to reduce traffic congestion and to generate revenue to fund MTA capital projects. The Long Island Rail Road and Metro North will each receive 10% of toll revenue, and NYC Transit, which includes subways and buses, will receive 80% of the toll revenue raised from the congestion pricing plan. Congestion pricing was originally slated to take effect in January 2021. In October 2019, the MTA announced that it had selected the technology company, TransCore, for a $507 million, seven-year contract to “design, build, operate and maintain” the infrastructure for the tolling.

The delays in implementation have been blamed on COVID-19 and political paralysis. Before New York State could implement congestion pricing, the plan needed to undergo an environmental review, and be approved by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). However, despite repeated requests from the state and city, the U.S. Department of Transportation under President Trump failed to provide such approvals, setting back the project for years. In March 2021, shortly after President Biden took office, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg gave the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) the green light to proceed with an environmental assessment to expedite the program’s start date.

In August, incoming N.Y. State Governor Kathy Hochul stated — through a spokesperson — that she “has supported congestion pricing in the past, but the pace and timing is something she will need to evaluate further given the constantly changing impact of COVID-19 on commuters.” She has since changed her tune, telling Politico, “I have supported, I do support and I will support — no question, my support for congestion pricing,” she said. “And I’ve already asked the question, how do we reduce the timeframe?” Yet, the MTA, which is under the governor’s control, has yet to appoint the members of the Traffic Mobility Review Board (TMRB) that is responsible for congestion pricing details, including rates and any further exemptions.

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, the Democratic party nominee and presumptive New York City Mayor, has declared his support for congestion pricing while expressing concerns about equity for low-income New Yorkers. Those concerns are driven by the current lack of viable alternatives to driving for many New Yorkers. Many areas of the outer boroughs lack viable public transportation options into Manhattan, which is why people rely on personal vehicles in the first place. Transit improvements and discounted rail fares are crucial to the congestion pricing deal. Shortly after the law passed, the MTA agreed to provide up to 20% commuter rail discounts to New York City residents not served by subways in northeast Queens. The MTA also agreed to put $3 million toward enhancing express bus service from Queens to Midtown. These projects are being funded, in part, by revenue from the for-hire vehicle and taxi congestion surcharge.

Where the Process Stands Now

Currently, the CBDTP is undergoing its FHWA Environmental Assessment in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to evaluate the potential environmental effects of the program. The Environmental Assessment process began at the end of August 2021, and is scheduled to take 16 months.

The process included more than 20 public meetings and outreach to Environmental Justice communities in relevant areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. These public meetings were held throughout September and October of this year. The feedback gathered in the public meetings will be part of the Environmental Assessment, which the FHWA will publish for public review. Following the release of the Environmental Assessment, the MTA will hold additional public meetings for comment specifically on the document. If the FHWA approves the proposed congestion tolling program, then it may go forward.

What the Proposed Tolling Program Looks Like

Through public meetings, the MTA has provided glimpses of what the CBDTP could look like. Under the CBDTP, vehicles that enter or remain in Manhattan’s Central Business District would be tolled. The technology developed by TransCore will need to track every vehicle entering and traveling through the tolling zone. If the FHWA approves the CBDTP, vehicles that enter or simply remain in the Central Business District would be tolled. The toll would be paid using an E-ZPass. For vehicles without an E-ZPass, a toll bill would be mailed to the address of the registered vehicle owner who would pay the bill through Tolls by Mail. Sensors and cameras would be located above the roadway on poles that look like those used for sidewalk lights or traffic lights. Toll rates will be determined by the MTA’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority Board, informed by recommendations of the Traffic Mobility Review Board, which will be issued after public hearings.

The Central Business District Tolling Zone would cover 60th Street in Manhattan and all the roadways south of 60th Street, except for FDR Drive, West Side Highway/9A, Battery Park Underpass, and any surface roadway portions of the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel connecting to West Street. In other words, if the vehicle is traveling north or south on the eastern or western highways, those vehicles “passing through” the Central Business District will not be subject to CBDTP.

When and How Toll Amounts Will Be Decided

A Traffic Mobility Review Board (TMRB) will recommend toll rates to the MTA’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority Board, which has final say on determining the final tolling rates. The MTA will appoint the board, which will be comprised of a chair and five members, one recommended by the NYC Mayor, and at least one member each residing in the Metro-North and Long Island service regions. On July 15, 2021, Mayor Bill de Blasio recommended Department of Finance Commissioner Sherif Soliman to the TMRB, and urged the MTA to appoint and convene the board, which it has yet to do.

In making its recommendation, the TMRB will be informed by a traffic study and will consider the ability to generate revenue required, impact on traffic patterns and volumes, public safety, and air quality and pollution. In addition, under the law, the CBDTP must:

- Charge passenger vehicles only once each day for entering or remaining in the CBD;

- Change the toll rates at set times or days (variable tolling). For example, during peak times, the toll for E-ZPass users could be $9–$23 and tolls by mail might be $14–$35. Off-peak will be less;

- Allow residents of the CBD making less than $60,000 to get a New York State tax credit for CBD tolls paid; and

- Not toll qualifying authorized emergency vehicles and qualifying vehicles transporting people with disabilities.

The Act also says the TMRB must recommend a plan for credits, discounts, and/or exemptions for tolls paid the same day on bridges and tunnels and FHV trips subject to the congestion surcharge. Toll rates will vary depending on the time of day, method of payment (E-ZPass or by mail), and the inclusion of credits, discounts, and/or exemptions. As credits, discounts, and/or exemptions are included there will be a need to increase the base tolling rate. At this time, the modeling is not complete. However, it has been reported that officials are planning on a congestion pricing amount somewhere between $9 and $23.

Once the TMRB recommends the toll rates, the TBTA will then follow its process for setting tolls, which includes a public hearing. That final decision on tolls will include the toll for each type of vehicle; how and when the tolls would change (variable pricing); and any other credits, discounts, and/or exemptions.

Congestion Pricing Exemptions

There are only two exemptions written into the legislation itself: emergency vehicles and vehicles transporting a person with a disability. The law leaves it to the MTA to decide the eligibility criteria for the disability exemption. The TMRB could recommend other credits, discounts, and exemptions. Since the law first passed, everyone from the freight hauling industry to motorcycle groups and off-duty police officers have argued the congestion charges should not apply to them. Every carve-out and exemption may make the price of commuting more expensive for everyone else. Too many exemptions and discounts would also undercut the goal of reducing congestion. As I told Bloomberg News in 2019, setting the criteria too broadly and subjectively could result in a sizeable exemption group, which could undercut the revenue benefits.

How to factor in tolls that motorists are already paying to cross bridges and tunnels into Manhattan is another big question that has yet to be answered. The MTA and Traffic Mobility Review Board are required to come up with a plan to address the issue, and it is possible that drivers will be charged twice with tolls because they are intended to fund separate projects. The congestion toll is going into an MTA “lockbox” to fund subway and commuter rails, while the existing crossing tolls were implemented to fund other projects. Reducing one toll to pay for another may not make sense fiscally for the MTA, which is under a mandate to use the congestion tolls to produce $15 billion in transit funding by 2024 – is a “zero sum game” that appears to be primarily revenue driven.

How Does the Congestion Surcharge Fit into Congestion Pricing?

Since February 2, 2019, taxi and FHV trips that begin, end, or pass through Manhattan below 96th Street have been subject to a congestion surcharge. The surcharge fees are $2.50 for taxis, $2.75 for for-hire vehicles, and 75 cents for app-based pooled rides of multiple passengers. The surcharge is also limited to intrastate trips, while there is no similar requirement on the toll program.

While the legislation provides that private passenger vehicles registered in New York will only be tolled once a day, this does not extend to taxis and other for-hire vehicles. Every trip into the CBD would be subject to the congestion toll and the congestion surcharge. A carve-out for FHV and taxi trips that are subject to the congestion surcharge did not make it into the congestion toll legislation, which simply calls for the mobility board to recommend a “a plan to address credits, discounts, and/or exemptions” for such trips based on factors including, but not limited to, initial market entry costs associated with licensing and regulation, comparative contribution to congestion in the CBD, and general industry impact.

Passengers might get a break from paying the congestion toll on top of the congestion surcharge on trips into the CBD. However, because the law addresses trips and not vehicles, taxis and FHVs entering the congestion tolling zone without a passenger will likely have to pay the toll to access Manhattan to look for fares.

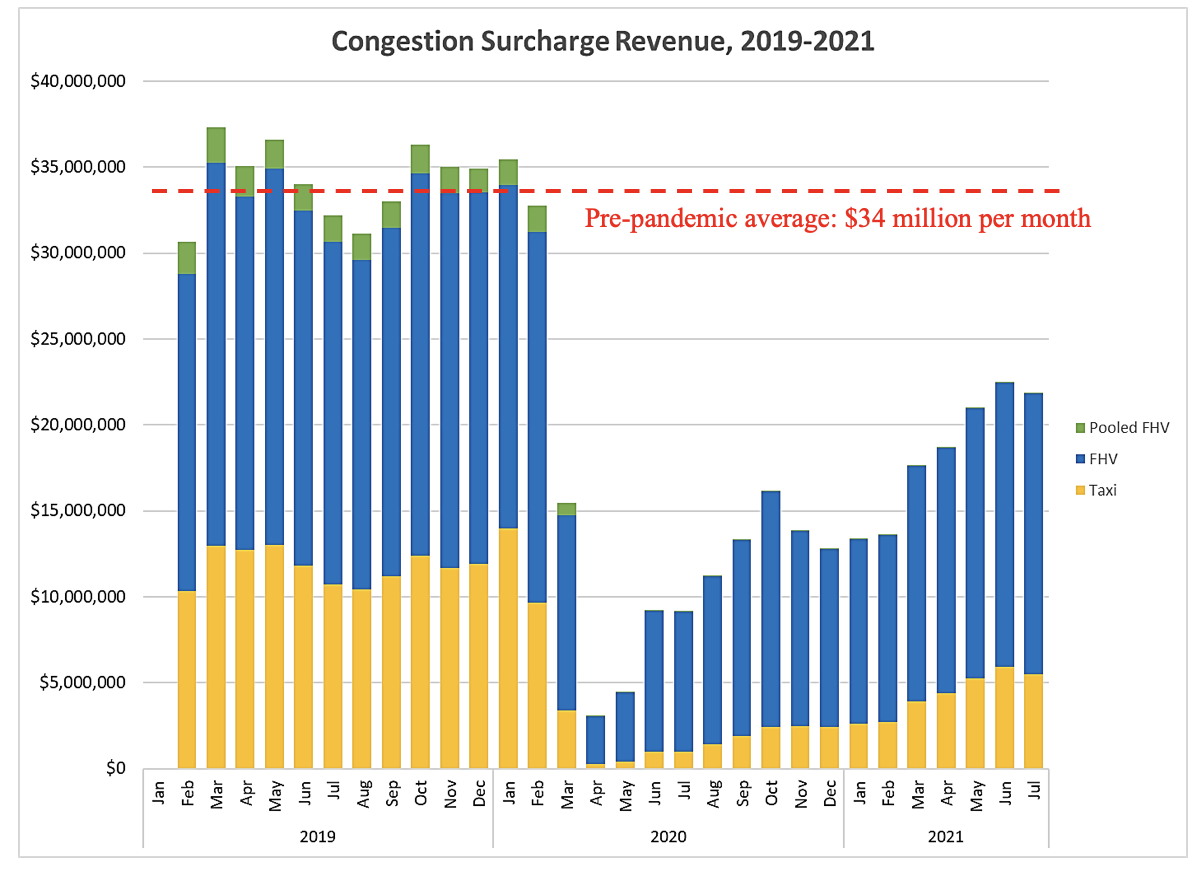

When initially implemented in 2019, the surcharge was expected to raise $400 million annually. Based on data from the NYS Department of Taxation and Finance, in 2019, the total revenue collected from the congestion surcharge was $376 million, but the collected fees dropped by more than one-half to $177 million in 2020 due to the pandemic. In 2021, the total revenue collected up until June was $107 million. The total collected by the end of 2021 will probably be approximately $250 million, which is roughly one-third less than 2019, and short of the expected $400 million.

As shown in the chart below, monthly revenue dropped significantly since March 2020. Although the revenue has recovered since the start of the pandemic, it shows no sign of hitting the pre-pandemic average of $34 million anytime soon. This is going to cause a permanent dent on the MTA’s budgeting, and may demotivate the agency from exempting taxis and FHVs from the tolling program.

Source: Work product of the author based on data obtained from NYS Department of Taxation & Finance through a FOIL request.

Modal Shift

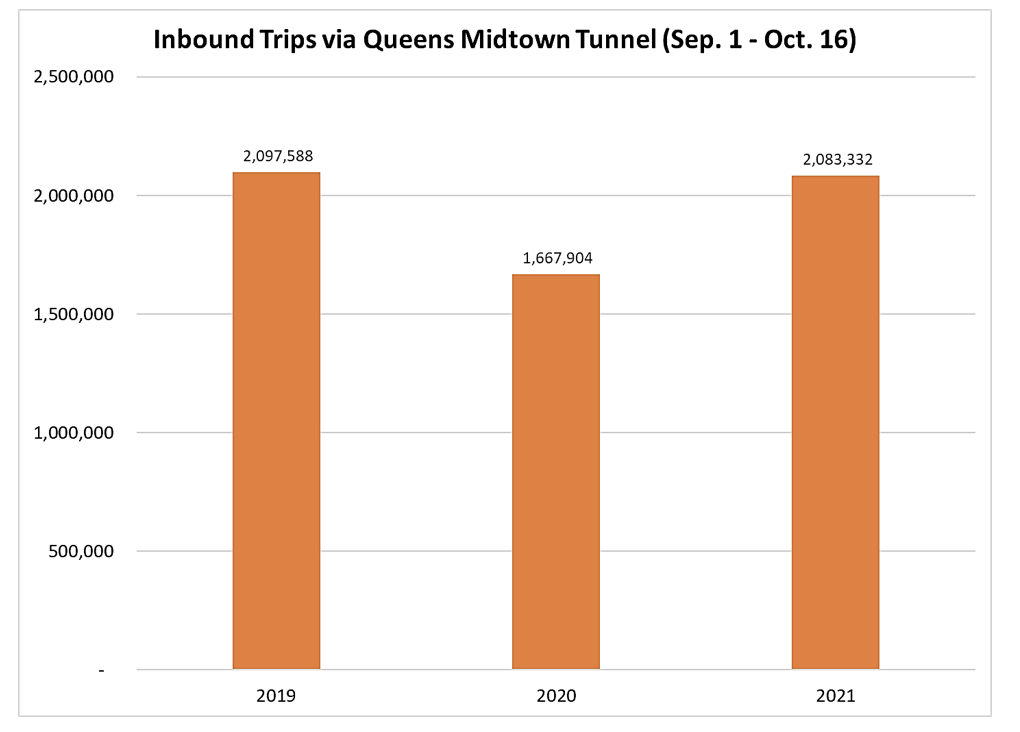

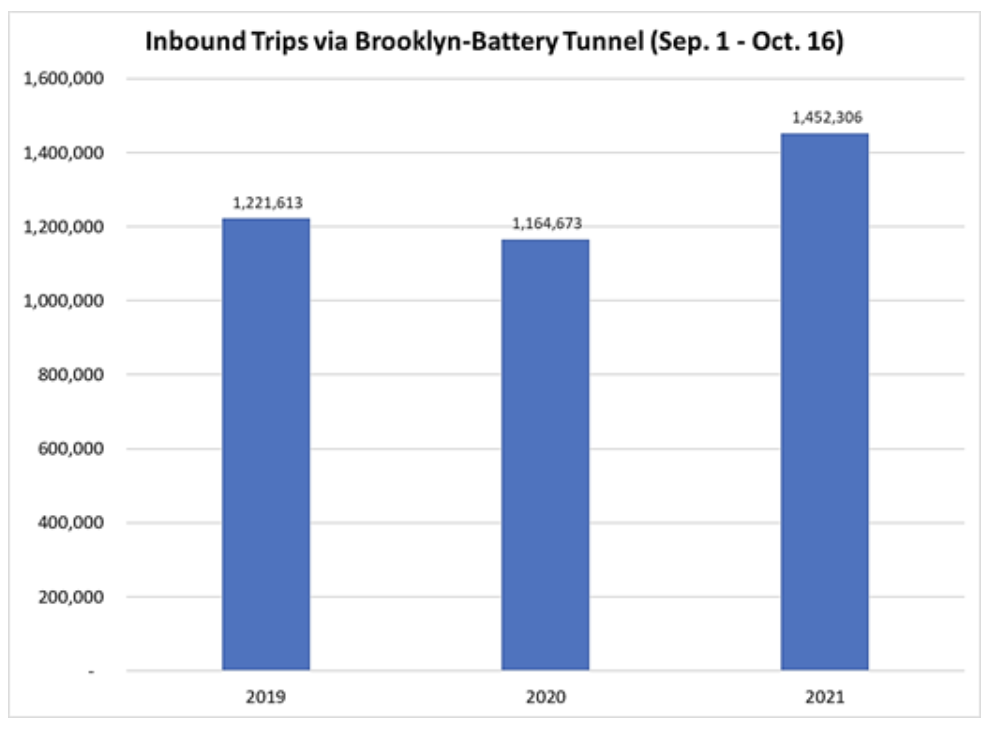

Over the past month and a half, inbound trips via the Queens Midtown and Brooklyn-Battery Tunnels have been close to pre-pandemic levels (see charts below). Both tunnels funnel cars directly into the proposed charging zone, signifying increased vehicle traffic in the CBD. As more workers return to their offices, the tunnel usage could even increase further, especially if those who commute into the city remain reluctant to take trains and the subways.

Source: Work product of the author with data from the MTA. https://data.ny.gov/Transportation/Daily-Traffic-on-MTA-Bridges-Tunnels/fcbp-umit

Source: Work product of the author with data from the MTA. https://data.ny.gov/Transportation/Daily-Traffic-on-MTA-Bridges-Tunnels/fcbp-umit

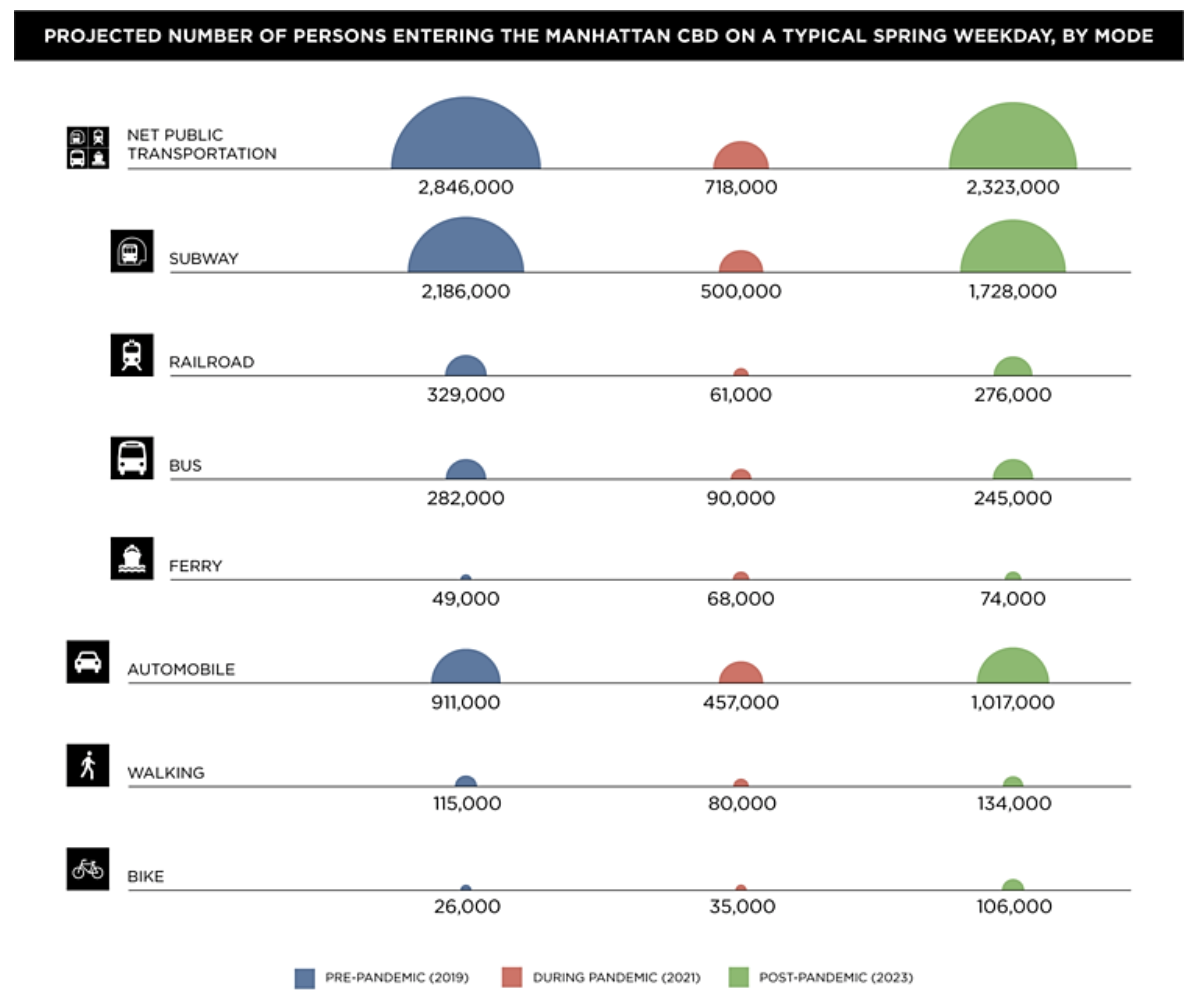

A recent study by Sam Schwartz Engineering and Clarion Research approximated an additional 90,000 vehicles entering the CBD daily by 2023, with the share of public transportation trips dropping. Overall, fewer people will travel into the CBD in the near future, but more of them will choose to get there by driving. As shown in the diagram below, the projected number of persons entering the CBD in 2023 via automobiles is expected to grow by 12%, while those using public transportation will drop by 18%. The pandemic has, no doubt, created longer-term changes to NYC’s public transit system. As of today, the subway, Metro-North Railroad, and LIRR ridership are still down 50% from pre-pandemic levels, and bus ridership is down 40%.

Source: “Manhattan Transfer: How Travel to the CBD will Change Post-Pandemic” (Clarion Research and Sam Schwartz Engineering)

Predictions & Ideas to Make NYC’s Congestion Pricing Plan Work Better!

Based on the current conditions, here are some cautious observations and predictions, as well as some ideas to help the system work better once in place. As the data above shows, congestion is bad and will almost certainly get even worse when everything reopens fully. It is going to be Carmageddon, or a Carpocalyspe, with commuters and visitors flocking to the city in cars in even bigger numbers. To reduce congestion, there must be viable alternatives for people to travel to and from NYC.

One way to reduce the number of vehicles in the Manhattan CBD and expand access to mass transit in the outer boroughs is to divert taxis and FHVs to the outer boroughs to provide first/last mile transportation to transit hubs. For many years, taxis have been paying an MTA surcharge to support their competitors – namely public transit. Now is the time to use subsidized taxis and liveries for first and last mile service in transit deserts. A portion of the lockbox money from congestion pricing could be devoted to the taxi and FHV industries that have suffered. The MTA could set up franchised taxi and FHV stands and/or connectors in the outer-borough to get even more people to use mass transit to commute to Manhattan, other areas of the City, and elsewhere. While outer-borough commuters represent only a small fraction of those who commute to jobs in Manhattan by vehicle, overwhelmingly these workers use mass transit to get to work in Manhattan and elsewhere. Regardless of their destination, outer-borough residents in transit deserts would benefit from congestion pricing that funds subsidized taxis and FHVs to get them to transit hubs.

As for private buses, they are a congestion solution. Each operating bus removes up to 55 cars off the road. These operators often serve areas in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut where no other viable mass transit option exists, making them crucial to reducing traffic congestion. Like taxis and FHVs, they are also subject to tolls more than once each day. These groups have all pleaded for an exemption from the new tolls. It makes no sense from a congestion mitigation standpoint to charge private buses, or shared ride services like Via for that matter. We should encourage shared mobility at all levels as an alternative to PMV usage.

Black cars, ride-hailing companies, and taxis already pay a congestion fee for driving in Manhattan. The law requires that the mobility board recommend a “a plan to address credits, discounts, and/or exemptions” for such trips based on factors including, but not limited to, initial market entry costs associated with licensing and regulation, comparative contribution to congestion in the CBD, and general industry impact. It is possible that FHV and taxi passengers might get a break, but I am not holding my breath on that one – given the enormous amount of revenue already generated for the MTA. In theory, taxis and FHVs really should be exempt as they are an alternative to PMV car usage. However, opponents of this exemption could argue that these vehicles accounted for over half of all vehicle miles travelled in the CBD before the pandemic, and it is possible that giving them an exemption would negatively impact the pricing scheme’s effectiveness, like it did in London. Since 2003, London has had a congestion pricing scheme, which initially exempted all for-hire vehicles (private-hire vehicles and black cabs) from the fees. As TNCs became increasingly popular, they diminished the pricing scheme’s effectiveness, leading London to remove the exemption for private-hire vehicles in 2019. London’s black cabs remain exempt. Let’s start by at least exempting: corporate shuttles and private buses in general; FHVs and taxis coming into the CBD to work without a passenger; and group rides or full vehicles (like an HOV 3 lane), and see if it works.

Of course, congestion pricing should not be an MTA cash grab to pour money into a system that is not working effectively for all people. The public should demand the money be earmarked for other clean air initiatives to work alongside other congestion mitigation measures or policies that can serve as a disincentive to PMV travel into the CBD. Some of the lockbox money should pay for electric buses and electric charging stations in the CBD, and electric vehicles should be exempt from the charges at program inception.

The pandemic has already arguably slowed down implementation of congestion pricing, but it seems the bigger deterrent was the Trump administration’s lack of support for the CBDTP. Now that that is no longer the case with the support of the Biden administration, the CBDTP seems like it will go forward according to the most recent revised scheduled. The Environmental Assessment process began at the end of August 2021, setting in motion a 16-month process to obtain federal approval for the project. Once the review is complete, FHWA will need to give it permission to proceed. Then, Transcore will have up to another 310 days to get the tolls underway. Transit officials expect the tolls to be up and running in 2023—conveniently after the next gubernatorial election in November 2022.

New York politicians are not the only ones worried about the political toll of congestion pricing. New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy and other Garden State politicians have objected to congestion pricing. New Jersey commuters fear they will have to pay the congestion toll in addition to the tolls they already pay to drive into Manhattan through the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels or over the George Washington Bridge. Even though the Act states the TMRB must recommend a plan for credits, discounts and/or exemptions for tolls paid the same day on bridges and tunnels, Murphy recently threatened to destroy the Port Authority unless New York ensures New Jersey commuters will not be double tolled. Politico reported that, at a recent meeting of the Morris County Chamber of Commerce, Murphy said he has “methods” to use against New York “that we will use if we have to — and I hope we don’t have to — including vetoing the minutes of the Port Authority, which is kind of a nuclear option, but if we have to, we’ll do it.” He also said “We’re not going to relent if New Jersey commuters are discriminated against, period.”

Going nuclear on the Port Authority is not the only threat lobbed at New York from across the Hudson. In August, New Jersey Congressman Josh Gottheimer introduced federal legislation, the Anti-Congestion Tax Act, “to stop New York mooching off hardworking jersey families,” according to a release from his office. The law would cut off certain federal grants to MTA projects until New Jersey drivers receive exemptions from the CBDTP. It would also give those drivers a federal tax credit equal to the amount they pay in tolls.

Borough President Eric Adams is on board with congestion pricing any may push for an expedited timeline, as the current mayor and other officials have already said that the proposed timeline is too long. With Hochul up for election, and congestion pricing being unpopular with voters, she may stick with the MTA’s timeline. So, get ready, because the CBDTP – in some form – is making its way to a Manhattan street near you!

Matthew W. Daus, Esq.

President, International Association of Transportation Regulators

http://iatr.global/

Transportation Technology Chair, City University of New York,

Transportation Research Center at The City College of New York

http://www.utrc2.org/

Partner and Chairman, Windels Marx Transportation Practice Group

http://windelsmarx.com

Contact: mdaus@windelsmarx.com

156 West 56th Street | New York, NY 10019

T. 212.237.1106 | F. 212.262.1215